Tag: Douglas-fir

Eugene’s Winter Trees

Our Favorite Trees to Watch in Winter

Many trees have shed their leaves and are on their way to being dormant for the winter. But not all of them! Late fall and winter in Oregon and Washington is still a wonderful time to admire trees. Our Eugene team put together some of their favorites to watch out for this time of year.

One of the most brilliant fall trees is the gingko, whose intense yellow leaves tend to fall all at once, thanks to their unique stems. Although ginkgos have “broad” leaves, they are actually more closely related to conifers. The modern ginkgo has changed little since its ancestors first graced the planet more than 200 million years ago—tens of millions of years before the advent of conifers and more than a hundred million years before broad-leafed trees became abundant.

For many the Douglas-fir, Oregon’s state tree, is a quintessential evergreen conifer, especially as many of them head into our living rooms for the holidays. Douglas-fir dominates local woodlands, and is joined sometimes by valley ponderosa pine, incense-cedar, and grand fir.

Conifers like the Doug-fir are perfectly adapted to our area’s wet winters and dry summers. Part of what makes Eugene special is that while the urban forest is composed largely of broad-leafed deciduous trees, it’s punctuated with firs, incense-cedars, giant sequoias and other conifers.

One of the many reasons we love evergreen conifers—they work year-round, producing oxygen and storing up carbon through photosynthesis, and providing important stormwater benefits by intercepting precipitation in their dense canopies.

Another favorite? The Atlas cedar, one of our true cedars. You can tell the cones of true cedars, like the atlas cedar, because they stick up vertically and shed their bracts one by one while staying attached to the tree.

The Atlas cedar notable is this time of year because it’s already releasing its pollen. Many conifers, in particular, “bloom” during late fall and winter. Atlas cedars (Cedrus atlantica) have exceptionally large and showy pollen cones, sometimes two to three inches in length and up to half an inch in diameter. The spent pollen cones are most noticeable after they have fallen, when they carpet the ground beneath the tree with what look like big, fuzzy, yellow caterpillars.

Keep in mind, wind pollinated trees are responsible for allergies, rather than showy flowers. Trees like the incense cedar will be putting out pollen in December. But the rain might save us—heavy rain will knock the particulates out of the air, cleaning them up for us.

Many people have the impression that, during the winter, trees—especially broad-leafed deciduous ones—are completely dormant. But thanks to relatively mild winters in western Oregon, it’s possible to find at least one species of broad-leafed tree—and sometimes several or more—in bloom during any given month of winter. In December, the long, dangling, pollen-bearing catkins of European filberts begin to develop—and the tiny, magenta female flowers do, too, though they’re not nearly as conspicuous. And in January, we begin to see the first elm flowers. Keep your eye out for these lovely signs of life!

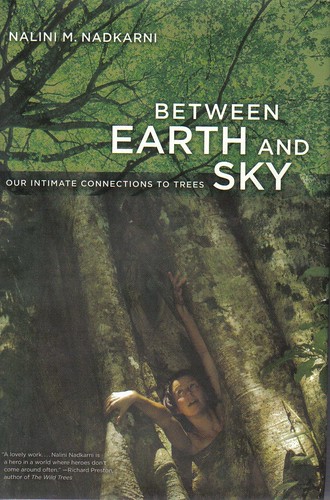

Between Earth and Sky, a book review

By Tom Atiyeh

Rarely could a book capture the spirit of my recent job transition as well as Nalini Nadkarni’s Between Earth and Sky.

The book was poignant for me as I moved from working at Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center, where staff members were stewards of thousand-year-old stands of Douglas-fir, Western Hemlock, Pacific Yew, and Western Redcedar, to my current work with the urban forest at Friends of Trees.

Between Earth and Sky was published in 2008, and it has taken me over a year to finish it, mainly for two reasons: I didn’t want it to end, and it helped me make the transition from the ancient to the urban.

A well-known environmental professor from Evergreen State College in Washington, Nadkarni weaves poetry and science to encompass forests from canopy to roots. Her view is similar to that of forest ecologist Dr. Jerry Franklin, who said at the conclusion of his recent Portland State University presentation, “There is as much life to explore below the surface as above.”

The 40 assembled poems and 20 pages of recommended reading in Nadkarni’s book will give the intrepid reader plenty to ruminate about and will inspire scholarly pursuits. Her anecdotes and reflections explain her own personal affinity for trees.

Trees and power lines: A bad idea?

By Brighton West

Someone recently asked why Friends of Trees planted trees under power lines, implying that it was a bad idea. Not so if you follow the rule “Right Tree in the Right Place.”

Trees have different types of growing habits. We know that Doug-Firs have a strong central leader (the main trunk goes straight up), Accolade Elms don’t (their branches all spread out and create a vase shape), and Prairiefire Crabapples only grow about 20 feet tall.

Knowing these characteristics, we can select a tree that doesn’t grow tall enough to interfere with primary power lines—and thus won’t need to be pruned by the power company.

I don’t know of many people who like to look at overhead wires, so selecting a low-growing tree to grow underneath the primary lines can be a good way to screen these lines from eye level. And if the lines aren’t primary power lines, a tall-growing tree could be the most effective—but more about that in my next blog post.

Coming next Monday: Trees and Powerlines: When is it OK to plant a tall tree under power lines?

West is the programs director at Friends of Trees: [email protected]; 503-282-8846 ext. 19

A tree walk through history in Laurelhurst Park

By Andy Meeks

On Wednesday morning approximately 30 people were treated to a walking tour highlighting the trees and history of Laurelhurst Park.

Phyllis Reynolds, author of “Trees of Greater Portland” and longtime Friends of Trees supporter, led the tour as part of the Portland Parks & Recreation’s (PP&R) Arbor Week.

Reynolds has done extensive research and mapping work in the Southeast Portland park and said that there are nearly 1,000 trees in the park consisting of almost 115 species, about one-third of which are Douglas-firs. She gave a very thorough, descriptive and entertaining walk past ginkgos, grand firs, the Concert Grove lindens, black oaks, sycamore maples, giant sequoias, Kentucky coffeetrees, white oaks and dawn redwoods.

The group learned from Reynolds that Laurelhurst Park was once part of the 462-acre Hazel Fern Farm owned by William Sargent Ladd, a native of Vermont who twice served as Portland’s mayor in the 1850s. He used it as a dairy farm and also raised Clydesdale draft horses and cattle. Ladd died in 1893 and his heirs sold the surrounding land to a group of developers who created the Laurelhurst neighborhood in conjunction with Frederick Law Olmsted’s landscape architecture firm.

Douglas-fir stories from The Oregonian

Oregon State researchers have found a fungal disease is strengthening its attack against Pacific Northwest Douglas-fir, reports The Oregonian.

An excerpt from the story:

The epidemic of Swiss needle cast stunts growth in both older and younger trees and appears to be unprecedented over at least the past 100 years, OSU researchers Bryan Black, David Shaw, and Jeffrey Stone concluded.

Swiss needle cast, which originated in Europe, has spread sharply since 1996. It affects hundreds of thousands of acres in Oregon and Washington, costing tens of millions a year in lost growth. It rarely kills trees but causes discoloration and loss of needles and stunts growth.

The researchers found that 376,000 acres were affected by the disease in 2008.

Also from The Oregonian late last month, a travel piece about the world’s tallest Douglas Fir in Coos County, and how the team from Ascending the Giants measured it in 2008.

–Toshio Suzuki