Tag: pests

Emerald Ash Borer

What we can do in response

The discovery of the emerald ash borer in Oregon has many people rightfully worried about the fate of ash trees in our region. The Emerald Ash Borer, or EAB, is an invasive wood boring beetle that feeds on ash trees. There are thousands of wood boring beetles in the world, and most cause no problems at all, but EAB isn’t native to North America, where it has fewer natural predators and the ash trees have no natural defenses.

EAB was first discovered on the North American continent in Southeastern Michigan in 2002, likely brought in with wood packing material. Since its introduction, it has caused catastrophic tree deaths and slowly spread across the continent.

EAB has likely already been in our area for a few years; the amount of time that it takes for a healthy ash tree to die from EAB is 3-5 years, that is why we are seeing some of the first trees in active decline right now.

Ash trees make up 5% of Portland’s street tree canopy (1 in every 20 trees!) and there are 9,000 ash trees on streets and in parks of Eugene (with many more that haven’t been inventoried). In certain areas the absence of ash will be more stark than others. We will particularly notice ash trees dying in large numbers in certain natural areas (the Oregon Ash, Fraxinus latifolia) and in parking lots, where they are a popular landscaping tree. It is important to know that preemptively removing ash trees in large numbers will not stop EAB. The ash trees we have, as long as we have them, provide tremendous benefits to us and our environments

In response to the EAB’s arrival, some Friends of Trees staff members are taking trainings, doing research, and formulating our best response to the EAB presence in our community.

“We have a huge community of people with tree knowledge,” says Green Space Specialist Harrison Layer. “If we can accurately take notice of trees in distress, we can make a difference.”

What we can do:

- Learn how to identify an ash tree.

- Destroy ash trees that have died from infestation.

- Give insecticide treatment to ash trees of distinction, important members of our community.

- Plant a diversity of species in their place.

- Find ash trees who do not succumb and appear resistant to Emerald Ash Borer, scientists need to know about these survivors with important genes!

“It gives me hope to think about finding trees that are resistant to EAB,” Harrison says. “It helps me imagine a future where we still have ash trees.” The USFS Dorena Genetic Resource Center south of Eugene has successfully bred disease resistance to blister rust in sugar and western white pines, and to Phytophthora lateralis for Port-Orford-cedar, giving hope for resistant strains of OR ash.

There are several natural predators of EAB, and EAB will likely cause a boom in native wildlife that eats EAB. Many birds, especially woodpeckers eat EAB larvae and pupae, and some native wasps have been documented to eat EAB larvae. Woodpecker activity on an ash is a hint that it could be infested with EAB. Sometimes blonde patches of sloughed off bark can be seen on the tree from woodpeckers, because EAB makes eating trails in the sapwood right under the bark surface.

EAB doesn’t infest ash trees less than 1-inch in diameter, meaning the ash we have planted in the Green Space Program the past couple planting seasons are immune for now.

Ash trees in decline will often feature defoliation from the top of the tree, epicormic growths (suckers from base), and have ‘D-shaped holes’ in their trunks. It is important to remember that the actual beetle can only be seen during its ‘flight period’ which is roughly between June 1st and August 30th.

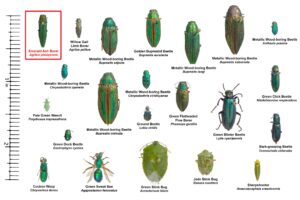

“There are many green beetles that are native to Oregon,” Harrison says. “So it’s really important to correctly identify the EAB Beetle.”

While an EAB has the ability to travel up to 50 miles in flight, it doesn’t usually travel more than 10 miles in a year; furthermore, they typically settle on the next ash tree that they find, which is often much less than 10 miles away. It will take decades before EAB run out of food in our region.

Again, it is important to know that removing ash trees in large numbers will not stop EAB. The ash trees can still provide tremendous benefits as long as we have them. We will need to monitor the situation as long as we can to learn, adapt, and hopefully one day recover.

Other resources:

- The Oregon Invasive Species Hotline is a great resource for people to report suspected ash trees suffering from EAB.

- Oregon Department of Agriculture – EAB Resources

- The Emerald Ash Borer – Untamed Science

- Oregon State University – Oregon Forest Pest Detector Training

Leaflet: Aphids

Aphids are everywhere, but don’t worry!

We’ve been getting a few inquiries about aphids this summer. And with the arrival of the emerald ash borer (a devastating issue we’ll keep you posted on), we have plenty of reasons to keep an eye out for pests. In the case of aphids, however, we don’t need to fret about them on our trees like we do in our veggie gardens.

In almost all instances, you don’t need to take any action—the tree can take care of itself. Aphids will only make a noticeable impact if the tree is still working to establish itself, or is somehow otherwise weakened. We often see them on Oregon ash, like the one pictured. If some wilting or crinkled leaves have you worried, here are some action steps you can take. Some folks might want to go straight to spraying, but pesticides really aren’t necessary to deal with aphids.

If you have more than just a few aphids on your leaves, the first thing to try is to just rinse them off with water. A good hose down will take care of a minor infestation. If that doesn’t quite do the trick, you can spray with soapy water. A treatment like this just once or twice a year will be enough.

If you see any ladybugs alongside the aphids, that’s great! Ladybugs will eat the aphids, and their larvae will really go to town feasting on them.

Aphids are everywhere—there are even tiny ones floating in the air we breathe. Some trees, like littleleaf linden, will have so many aphids that you may feel a mist of aphid “honeydew” when you walk underneath. You guessed it, that’s aphid poop. Just think of it as a nice reminder that trees are part of a larger ecosystem of living things.